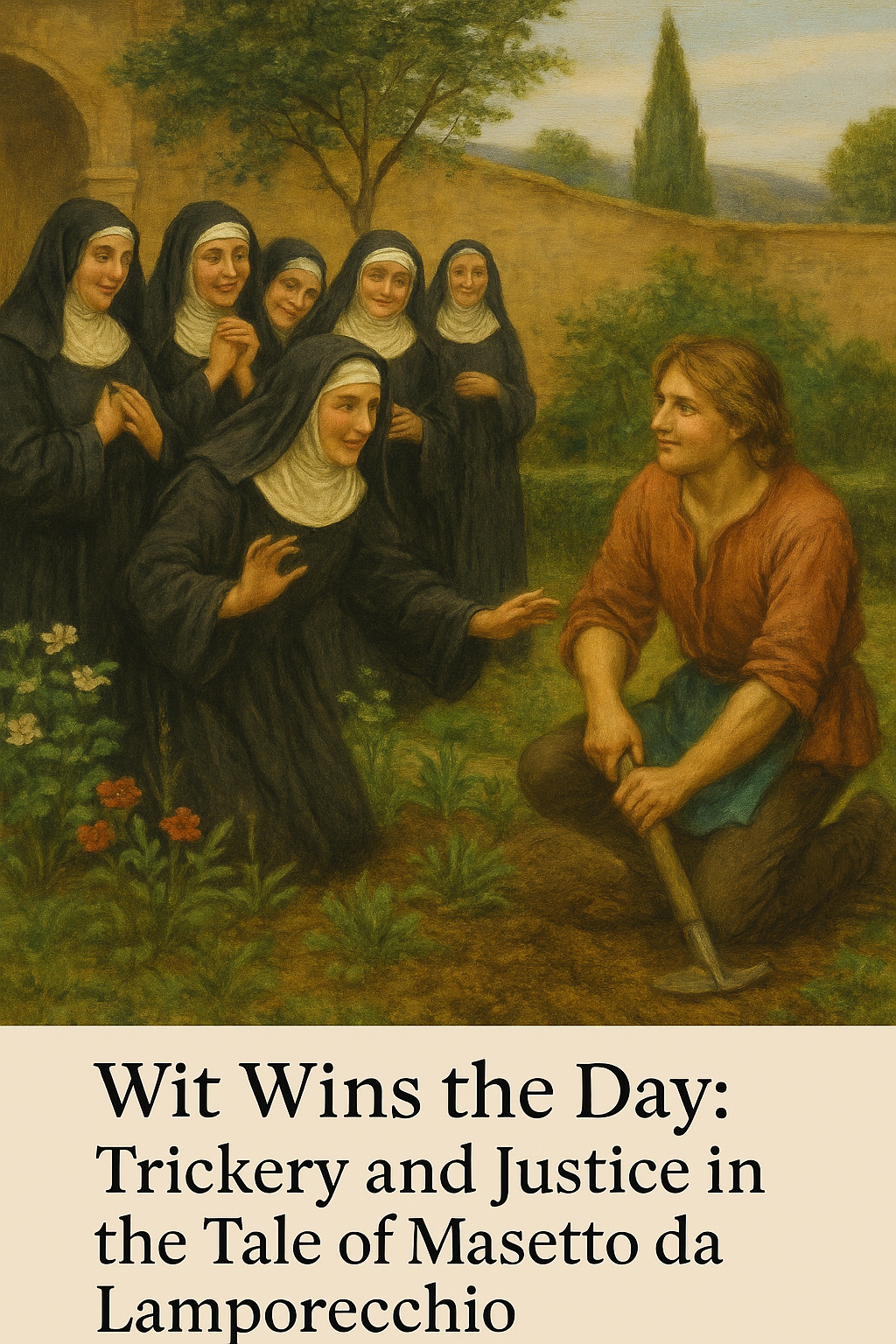

Wit Wins the Day: Trickery and Justice in the Tale of Masetto da Lamporecchio

“The one who is thought powerless may often hold the greatest power of all.”

— Inspired by The Decameron, Day 3, Tale 1

Introduction

Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a 14th-century masterpiece, presents a colorful tapestry of human experiences through 100 tales told by a group of young nobles fleeing the plague. Each story offers wit, insight, and critique. One of the most humorous and subversive entries is the tale of Masetto da Lamporecchio, a peasant who pretends to be mute in order to work at a convent—and finds himself at the center of unexpected temptation. Both comic and clever, this tale uses laughter to deliver sharp commentary on power, gender, and religious hypocrisy.

Summary: Masetto’s Scheme

Masetto, a handsome young laborer, realizes he won’t be hired by the nuns of a convent if they believe him capable of “worldly temptation.” So, he feigns being deaf and mute to appear safe. The plan works: Masetto is hired as a gardener. Over time, the nuns, believing he cannot speak or tattle, begin to seduce him. What begins with one nun turns into an open secret, and soon Masetto is exhausted by their collective desires. Eventually, he “regains” the power of speech and confesses—but instead of dismissal, he receives silent approval to stay. He lives out his days comfortably, respected and secretly central to the convent’s inner affairs.

Literary Analysis

Comic Irony and Power Reversal

At the heart of this tale is Boccaccio’s signature use of irony. Masetto gains power not through force, status, or wealth—but through silence and wit. He uses what the world sees as a weakness to subvert expectations and elevate his position in society. The humor lies in how this reversal unfolds: a mute man outsmarts an entire religious order.

Critique of Religious Institutions

Boccaccio’s tale does not vilify the nuns, but rather humanizes them, revealing how religious life can suppress natural desires. Their actions suggest the absurdity of expecting human beings to deny such fundamental instincts indefinitely. The convent, supposed to be a haven of purity, becomes a site of secret pleasure, complicity, and unspoken arrangements.

Gender Roles and Agency

The tale also flips gender expectations. The nuns become the initiators, and Masetto becomes the object of desire—overwhelmed, but not powerless. This role reversal adds to the comedic tone but also opens space for a proto-feminist reading, where women express sexual agency in a world designed to suppress it.

The Trickster Archetype

Masetto joins the ranks of literary tricksters who, like Odysseus or Reynard the Fox, use cunning over might. His cleverness isn't punished; it’s rewarded. Boccaccio seems to celebrate adaptability as a necessary virtue in a flawed world—especially for the poor or powerless.

Personal Reflection

Reading this tale felt like watching a perfectly timed comedy with a strong moral undercurrent. Masetto’s situation is outrageous, yet strangely sympathetic. I laughed at the absurdity, but I also admired how Boccaccio weaves criticism into comedy. The tale made me think about how power often disguises itself—and how those perceived as weak can change the game when they stop playing by the rules. In some ways, it reminds me of modern stories where underdogs manipulate the system to expose its flaws.

Conclusion

The tale of Masetto da Lamporecchio is more than just bawdy medieval humor—it’s a satire on power, purity, and survival. Boccaccio cleverly invites us to question institutions, reflect on human nature, and laugh at the chaos that ensues when desire meets deception. Over 600 years later, the story still resonates—not just for its entertainment value, but for its timeless truths.