A Falcon, A Fool, and A Fortune: Sacrifice and Redemption in Federigo’s Falcon

Introduction:

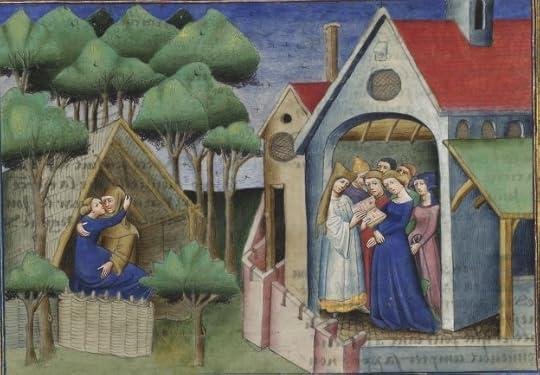

Giovanni Boccaccio’s "Federigo’s Falcon" from "The Decameron" is a poignant tale of unrequited love, self-sacrifice, and eventual reward, set against the backdrop of 14th-century Italian society. In this deceptively simple narrative, Boccaccio explores the dignity of love, the tragedy of wasted wealth, and the bittersweet irony of timing. This review argues that Federigo’s tale is not merely about a man and his falcon, but a commentary on virtue, class, and the value of authentic emotion in a world dominated by social expectation.

Summary:

Federigo, a young nobleman, squanders his fortune trying to win the heart of the beautiful but indifferent Monna Giovanna. Eventually reduced to poverty, he retreats to a small farm with only his prized falcon for company. When Monna’s son falls ill and requests the falcon, she visits Federigo to ask for it. Unaware of her true purpose, Federigo, having nothing else to offer, cooks the falcon as a meal for her. Upon learning of his sacrifice, Monna is deeply moved. After her son’s death, she eventually marries Federigo, acknowledging his noble character despite his material poverty.

Analysis:

At the heart of this tale is "sacrifice", both tragic and noble. Federigo’s decision to kill the very falcon Monna came to request is a masterstroke of dramatic irony. Boccaccio crafts this moment with emotional precision, evoking sympathy for a man whose love has blinded him to practical wisdom. The falcon, once a symbol of aristocratic leisure and masculine prowess, becomes a symbol of "selfless devotion", and its literal consumption marks the turning point in Federigo’s fate.

The characters are archetypes, yet they resist simplification. Federigo embodies the courtly lover—honorable, generous to a fault, and utterly sincere. His downfall stems not from vice, but from "a kind of noble foolishness", a theme that resonates with medieval ideals of chivalry and devotion. Monna Giovanna, initially aloof and bound by societal expectations, transforms into a figure of compassion and gratitude. Her decision to marry Federigo after her son's death suggests a deeper moral: true worth lies not in wealth but in "virtue and intention".

Boccaccio’s use of "irony" is subtle but powerful. The timing of events—the request for the falcon coming only after it’s been served as dinner—creates a tension between fate and choice, underscoring how human intentions can be tragically misaligned with outcomes. There's also a quiet "satire of class structures": Federigo, once noble but now poor, is morally rich; Monna, still wealthy, comes to see the emptiness of material status when faced with genuine love.

The tale also reflects "14th-century concerns": the fragility of life (evident in the boy’s illness), the rigidity of social class, and the expectations placed on women, especially widows. Yet its themes remain startlingly relevant. In an era of performative gestures and transactional relationships, Federigo’s sincerity—and Monna’s ultimate recognition of it—feels refreshingly authentic. Their union defies the superficial measures of status and wealth, offering a hopeful vision of emotional honesty winning over social convention.

Personal Response:

What struck me most about "Federigo’s Falcon" was its emotional restraint. The tale doesn’t rely on melodrama but instead builds quiet tension through gestures and timing. Federigo’s sacrifice felt both noble and tragic—an act of love that speaks louder than any grand declaration. I found myself admiring his unwavering character, and while Monna’s change of heart came late, it felt earned. I genuinely enjoyed the story's balance of heartbreak and hope, and its elegant moral lingered with me long after reading.

Conclusion:

"Federigo’s Falcon" endures because it speaks to timeless truths about love, sacrifice, and human dignity. Boccaccio invites us to consider not what people possess, but who they are at their core. In Federigo, we find a man who loses everything but retains his honor—and in Monna, a woman who learns to see value beyond wealth. Their story reminds us that in love, as in life, the greatest offerings often come from those who have the least to give—except, of course, their whole heart.