"Fortune’s Fool or Master of Wit? Trickery and Class in the Tale of Ciapelletto"

Introduction

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron opens with the tale of Ser Ciapelletto, a notoriously immoral man whose lies are so convincing that he’s venerated as a saint after death. It’s a story filled with paradox, irony, and social critique. In this review, I argue that Boccaccio uses Ciapelletto’s deception not just for comic effect, but to question the reliability of appearances, especially in matters of religion, morality, and class.

Summary

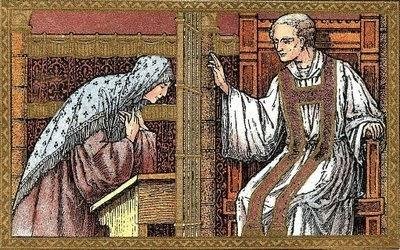

The tale follows Ser Ciapelletto, a corrupt and dishonest notary who finds himself terminally ill while staying with two Florentine merchants in Burgundy. Afraid that his reputation will bring scandal to their home, the merchants urge him to confess. Ciapelletto, unwilling to die disgraced, gives a hilariously exaggerated false confession to a naïve friar, claiming a life of saint-like virtue. The friar, completely fooled, praises him as a holy man. After his death, Ciapelletto is honored as a saint, and miracles are said to occur at his grave.

Analysis

This tale immediately sets the tone for the rest of The Decameron: witty, ironic, and morally complex. Boccaccio doesn’t condemn or punish Ciapelletto; in fact, he rewards him with sainthood, raising questions about how truth and virtue are constructed.

One of the most fascinating elements is how religion and reputation are manipulated. Ciapelletto’s confession is a performance tailored to match the friar’s expectations. His false humility—claiming he fasted often, never swore, and only lied once as a child—paints a caricature of piety. But it works because people want to believe in clear moral heroes. Boccaccio suggests that religious institutions are not only fallible but vulnerable to flattery and appearances.

The tale also critiques the social assumptions about class and character. Ciapelletto is from the professional class, yet he behaves worse than the peasants many might judge harshly. The friar’s admiration shows how easy it is to accept sanctity from someone who fits the mold—even when it’s undeserved. Here, Boccaccio is subtle but cutting: he implies that people often worship not true virtue but a convincing performance of it.

There’s also dark comedy in how Ciapelletto’s lies lead to sincere devotion. Boccaccio seems to relish the tension between truth and belief. Is the friar evil for spreading a lie, or simply gullible? Is Ciapelletto damned, or has he somehow tricked his way into grace? These contradictions make the tale rich for interpretation—and surprisingly modern.

Personal Response

I was surprised by how sharp and funny this tale is, even centuries later. It made me reflect on how easily people today are still swayed by image over substance—whether in politics, religion, or media. Ciapelletto isn’t likable, but he’s compelling, and that’s what makes the story effective. It reminded me that morality in literature isn’t always black and white, and that ambiguity can be the most powerful storytelling tool.

Conclusion

The tale of Ser Ciapelletto sets the stage for The Decameron’s exploration of human behavior in all its messy, contradictory brilliance. By giving a liar the legacy of a saint, Boccaccio isn’t simply mocking the church—he’s challenging us to question how we define good and evil, and who gets to do the defining. In today’s world of curated images and viral reputations, his message feels surprisingly timely.

#TheDecameron #Boccaccio #LiteraryReview #MedievalLiterature #Irony #ReligionAndMorality

Introduction

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron opens with the tale of Ser Ciapelletto, a notoriously immoral man whose lies are so convincing that he’s venerated as a saint after death. It’s a story filled with paradox, irony, and social critique. In this review, I argue that Boccaccio uses Ciapelletto’s deception not just for comic effect, but to question the reliability of appearances, especially in matters of religion, morality, and class.

Summary

The tale follows Ser Ciapelletto, a corrupt and dishonest notary who finds himself terminally ill while staying with two Florentine merchants in Burgundy. Afraid that his reputation will bring scandal to their home, the merchants urge him to confess. Ciapelletto, unwilling to die disgraced, gives a hilariously exaggerated false confession to a naïve friar, claiming a life of saint-like virtue. The friar, completely fooled, praises him as a holy man. After his death, Ciapelletto is honored as a saint, and miracles are said to occur at his grave.

Analysis

This tale immediately sets the tone for the rest of The Decameron: witty, ironic, and morally complex. Boccaccio doesn’t condemn or punish Ciapelletto; in fact, he rewards him with sainthood, raising questions about how truth and virtue are constructed.

One of the most fascinating elements is how religion and reputation are manipulated. Ciapelletto’s confession is a performance tailored to match the friar’s expectations. His false humility—claiming he fasted often, never swore, and only lied once as a child—paints a caricature of piety. But it works because people want to believe in clear moral heroes. Boccaccio suggests that religious institutions are not only fallible but vulnerable to flattery and appearances.

The tale also critiques the social assumptions about class and character. Ciapelletto is from the professional class, yet he behaves worse than the peasants many might judge harshly. The friar’s admiration shows how easy it is to accept sanctity from someone who fits the mold—even when it’s undeserved. Here, Boccaccio is subtle but cutting: he implies that people often worship not true virtue but a convincing performance of it.

There’s also dark comedy in how Ciapelletto’s lies lead to sincere devotion. Boccaccio seems to relish the tension between truth and belief. Is the friar evil for spreading a lie, or simply gullible? Is Ciapelletto damned, or has he somehow tricked his way into grace? These contradictions make the tale rich for interpretation—and surprisingly modern.

Personal Response

I was surprised by how sharp and funny this tale is, even centuries later. It made me reflect on how easily people today are still swayed by image over substance—whether in politics, religion, or media. Ciapelletto isn’t likable, but he’s compelling, and that’s what makes the story effective. It reminded me that morality in literature isn’t always black and white, and that ambiguity can be the most powerful storytelling tool.

Conclusion

The tale of Ser Ciapelletto sets the stage for The Decameron’s exploration of human behavior in all its messy, contradictory brilliance. By giving a liar the legacy of a saint, Boccaccio isn’t simply mocking the church—he’s challenging us to question how we define good and evil, and who gets to do the defining. In today’s world of curated images and viral reputations, his message feels surprisingly timely.

#TheDecameron #Boccaccio #LiteraryReview #MedievalLiterature #Irony #ReligionAndMorality

"Fortune’s Fool or Master of Wit? Trickery and Class in the Tale of Ciapelletto"

Introduction

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron opens with the tale of Ser Ciapelletto, a notoriously immoral man whose lies are so convincing that he’s venerated as a saint after death. It’s a story filled with paradox, irony, and social critique. In this review, I argue that Boccaccio uses Ciapelletto’s deception not just for comic effect, but to question the reliability of appearances, especially in matters of religion, morality, and class.

Summary

The tale follows Ser Ciapelletto, a corrupt and dishonest notary who finds himself terminally ill while staying with two Florentine merchants in Burgundy. Afraid that his reputation will bring scandal to their home, the merchants urge him to confess. Ciapelletto, unwilling to die disgraced, gives a hilariously exaggerated false confession to a naïve friar, claiming a life of saint-like virtue. The friar, completely fooled, praises him as a holy man. After his death, Ciapelletto is honored as a saint, and miracles are said to occur at his grave.

Analysis

This tale immediately sets the tone for the rest of The Decameron: witty, ironic, and morally complex. Boccaccio doesn’t condemn or punish Ciapelletto; in fact, he rewards him with sainthood, raising questions about how truth and virtue are constructed.

One of the most fascinating elements is how religion and reputation are manipulated. Ciapelletto’s confession is a performance tailored to match the friar’s expectations. His false humility—claiming he fasted often, never swore, and only lied once as a child—paints a caricature of piety. But it works because people want to believe in clear moral heroes. Boccaccio suggests that religious institutions are not only fallible but vulnerable to flattery and appearances.

The tale also critiques the social assumptions about class and character. Ciapelletto is from the professional class, yet he behaves worse than the peasants many might judge harshly. The friar’s admiration shows how easy it is to accept sanctity from someone who fits the mold—even when it’s undeserved. Here, Boccaccio is subtle but cutting: he implies that people often worship not true virtue but a convincing performance of it.

There’s also dark comedy in how Ciapelletto’s lies lead to sincere devotion. Boccaccio seems to relish the tension between truth and belief. Is the friar evil for spreading a lie, or simply gullible? Is Ciapelletto damned, or has he somehow tricked his way into grace? These contradictions make the tale rich for interpretation—and surprisingly modern.

Personal Response

I was surprised by how sharp and funny this tale is, even centuries later. It made me reflect on how easily people today are still swayed by image over substance—whether in politics, religion, or media. Ciapelletto isn’t likable, but he’s compelling, and that’s what makes the story effective. It reminded me that morality in literature isn’t always black and white, and that ambiguity can be the most powerful storytelling tool.

Conclusion

The tale of Ser Ciapelletto sets the stage for The Decameron’s exploration of human behavior in all its messy, contradictory brilliance. By giving a liar the legacy of a saint, Boccaccio isn’t simply mocking the church—he’s challenging us to question how we define good and evil, and who gets to do the defining. In today’s world of curated images and viral reputations, his message feels surprisingly timely.

#TheDecameron #Boccaccio #LiteraryReview #MedievalLiterature #Irony #ReligionAndMorality

0 Commentaires

·0 Parts

·235 Vue

·0 Aperçu